4×18: Metareference

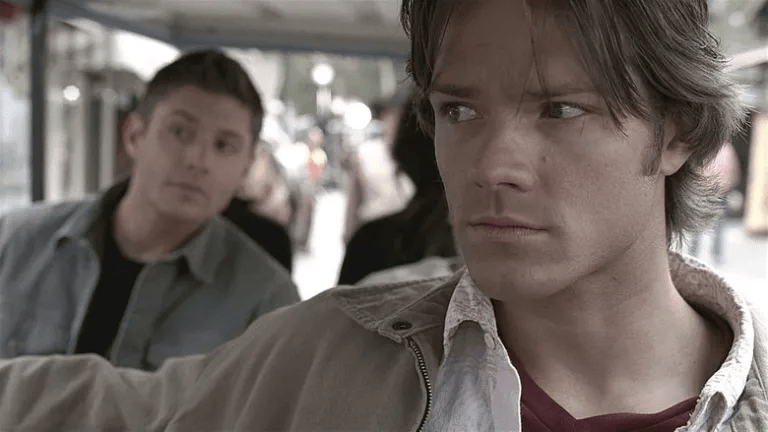

Already apparent in this partial synopsis of the episode is the high degree of metareference that has to this point been mostly absent from the show. Supernatural has certainly referred to itself before: for example, in “Hollywood Babylon” (2×18) when they pass the sound stage in which Gilmore Girls was filmed, Sam makes a face, referring to the fact that the actor Jared Padalecki who plays him had previously starred in the show. However, the presence of the Supernatural books and Chuck as their author takes the show’s metareference to a new level.

Werner Wolf, in the introduction to Metareference across Media, defines metareference as a form of self-reflection that “establishes a secondary reference to texts and media (and related issues) as such by…viewing them ‘from the outside’ of a meta-level from whose perspective they are consequently seen as different from unmediated reality and the content of represented worlds” (22-23). In other words, metareference is when a text reveals itself to be a text, that is, a constructed representation. In that way, we might understand metareference as functioning to pull the audience out of their immersion in the storyworld, to recognize the narrative as a narrative, and to interrogate the structures and processes that produce it.

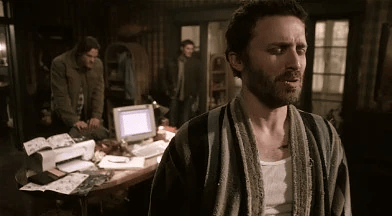

In Supernatural, “The Monster at the End of This Book” performs that function and opens the rest of the show up to unprecedented metareferential possibilities. In particular, the audience is called, through Chuck’s presence, to see Sam and Dean as characters whose stories have been authored. But they have not just been authored by any Joe Schmo off the street. As is revealed later in the episode, Chuck is a prophet of the Lord, a conduit for the Word of God. In that way, we can (possibly) understand their story as being authored, in the world of the show, by God himself, with Chuck as merely the one translating that story onto the page.

On another level, though, their existence as characters within a larger narrative—in this case, the “Winchester gospels”—calls attention to their existence as characters within a larger narrative in the TV show Supernatural. While the show had been, narratively speaking, an “episodic procedural drama” with overarching “iterative macro-questions,” season 4 signals a gradual shift toward “serialized narrative threads” (Favard 21). Sam and Dean, rather than simply brothers going on weekly adventures across the country, were beginning to be understood as characters in a much grander, more globally significant story. This shift toward arc storytelling is bolstered by the show’s creator and showrunner Eric Kripke’s insistence on a “five-year plan” (Favard 21).

If we read Chuck, as many do, as a stand-in for Kripke himself, then we can see the ways that the show grapples with itself as a show on a metareferential level, with Chuck/Kripke situated as the author—one who engages directly with his fans, characters, and the story itself. Furthermore, this, paired with Chuck’s relationship with God, provokes questions about the author’s relationships with audience, character, and text.

What, then, are the (meta)narrative implications of Chuck’s character?