5×22: Death of the Author

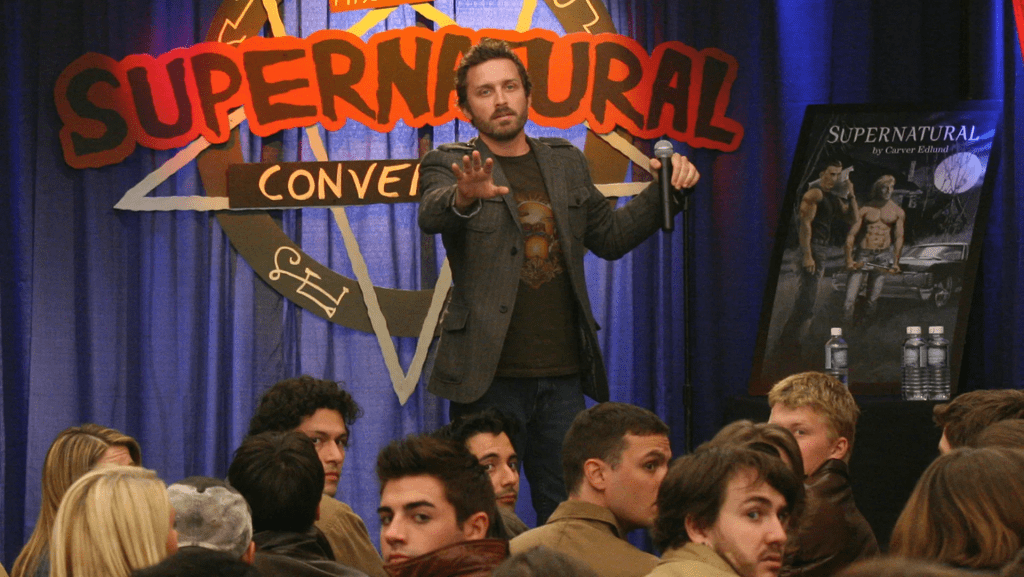

Whether Chuck is a prophet or God, the season 5 finale leaves ambiguous. If he is, Fathallah suggests, we might consider him “a literal manifestation of the originating deity Barthes recognizes as standing behind the authority of the Author” (159). If not, she contends, “then God is definitively absent or non-existent in Supernatural’s apocalyptic storyline” (159). I disagree with her insistence that Chuck not being God removes God from the playing field—we are told that Chuck, as a prophet, is a conduit to His word, and that since Chuck actively writes according to his visions from God, God has a stake in the action even if not manifestly present. Regardless of his status, the idea of Chuck as the embodiment of Barthes’s conception of the Author is particularly useful because, visible or not, God’s authority supports and legitimates Chuck’s text as “canonical truth” (Fathallah 161).

Either way, this episode does indicate that Chuck’s active role as a character in the narrative is over, and his dual function as diegetic author and narrator also end. We are thus asked to think of him as no longer involved in the story in any way. We must ask, then, if Chuck has been the show’s author the entire time (after all, his books consisted of the entirety of the show up to this point), what happens when the author disappears (or, as Barthes would say, dies)?

In one sense, Chuck’s disappearance signals not the end of the story, or even authorship per se, inasmuch as it signals the end of Kripke’s involvement in its production. The “original” creator and showrunner had finished his “five-year” narrative, and he would pass the torch to a new showrunner to take the show in new directions. In other words, “this could be read as the Author-God writing himself out of the text, to continue without him” (Fathallah 166). However, in another sense, it “imbues what Chuck/Kripke has written with the aura of magic and omnipotence,” positioning alternatives or revisions to this canon (on the part of fans, in particular) “as secondary and derivative” (166). On the level of the show, Chuck’s disappearance (and Kripke’s departure) signals the end of a “complete” narrative with a beginning, middle, and end, and the beginning of a “post-Author-God era” (Fathallah 158). We might, then, see this deification of Chuck/Kripke—far from Barthes’s vision of the “birth of the reader” (148)—as an exertion of power over the story as the sole arbiter of its “truth,” foreclosing alternatives and, we might say, limiting freedom.

And yet, this God-Author does disappear, either through the disappearance of God himself or his mouthpiece. And, despite the finality of Chuck’s statement, the episode doesn’t end there—the last scene is not Chuck’s disappearance but rather a cliffhanger to tease the start of the next season (Sam’s return from Hell). Chuck himself, as he signals a definitive end to his narrative, suggests that “nothing ever really ends.” This internal tension—the notion that these first five seasons are a self-contained narrative and the insistence that the story doesn’t end there—pushes the show’s metareference into the realm of a struggle with authorship and seriality.