5×22: Authorship and Seriality

The metareferential equation between the Supernatural books and the show frames the latter as a single-authored entity. As such, when the author of Supernatural disappears at the end of “Swan Song,” we are inevitably left wondering how the story can continue. If there is no author, from where can the narrative issue? This absence forces us to consider the show beyond the constraints of a series of novels, a medium generally consisting of a single-authored narrative, and to think about it as a serial TV show.

Of course, the show has never figured itself as a series of novels in a literal sense—it knows it’s a show, and it tells us that. For example, in the episode “Changing Channels” (5×8), the archangel Gabriel (Richard Speight Jr.) forces Sam and Dean to “play their roles” in a variety of television genres to encourage them to “play their roles” as the vessels of Lucifer and Michael, respectively, in the larger apocalyptic narrative. And yet, the show’s primary metareference to authorship with regards to the brothers’ story is the single-authored book series. By placing the show in the context of these two genres, it reveals an internal tension between the notion of authorship that Chuck represents (and that Kripke envisions through his “five-year plan”) and the radically different processes of production and consumption that characterize a serial television show.

Frank Kelleter provides a helpful framework through which to conceptualize seriality. Popular seriality, he argues, derives from the tension between the “two basic impulses of storytelling—the satisfaction of conclusion and the appeal of renewal” (9). He proposes five related definitions through which to understand popular series in relation to these impulses, two of which are particularly relevant to our discussion. First, popular series are distinct from the “work or oeuvre” in that they are “open” rather than “finished,” and they can be conceptualized as “evolving narratives” because their processes of production and reception “are intertwined in a feedback loop” (12-13). In other words, episodes are produced, released, and received by audiences, who then provide feedback, which then influences the production of the following installment, and so on and so forth. As a result, “serial audiences…become involved in a narrative’s progress” (13).

We see this play out most obviously in Supernatural through the show’s metareferences to its fans, through characters like Becky (Emily Perkins) and Chuck and through engagement with “slash fans” like in “The Monster at the End of This Book.” This notion of a production/reception feedback loop, then, poses a challenge to the idea of a singular author constructing the “complete” narrative from the beginning. Instead, it suggests that popular series like Supernatural are “moving targets,” their narrative trajectories shifting as they receive feedback from fans and the market (14).

Second, Kelleter contends that popular series must simultaneously “always project a finished story-text,” or an ending on the horizon, while ensuring that the “actuality of compositional finish…remain[s] inaccessible” (17). In other words, the show must have a strong enough narrative thrust toward a conclusion while preventing us from ever reaching that conclusion because then the series would end and no longer make money. As such, it takes on a “recursive character”: it engages in the “continual readjustment of possible continuations to already established information” (17). In “Swan Song,” we see this impulse at work: even as the “five-year plan” comes to an end, the show alludes to a new continuation of the narrative by bringing Sam back from Hell, thus enticing viewers to keep watching to see how that happened and what will be in store for the boys next. Chuck’s final line (“But then again, nothing ever really ends, does it?”) signals this internal tension—ensuring a satisfying conclusion while suggesting the possibility for the narrative’s continuation.

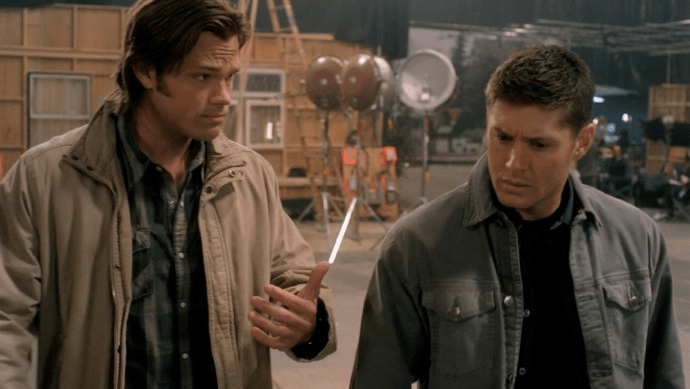

Chuck’s character, and his disappearance at the end of season 5, then, makes visible the underlying tensions between the notion of a single-authored, self-contained narrative and the ongoing, recursive processes of production and reception that characterize a popular (television) series. This tension challenges the singular dominance of the God-Author figure who plans and controls the narrative from a spatiotemporal distance, suggesting instead that the narrative is shaped in real-time through the engagement between various actors, which is further emphasized in episodes like “The French Mistake” (6×15). As such, seriality suggests the possibility of more narrative freedom, perhaps at the expense of coherence or consistency at times.

And yet, Chuck’s character, as the voice of God one way or another, suggests that the show is fundamentally troubled by this unstable narrative condition—“Swan Song” sides thematically with free will, but the narrative determinacy and closure that characterizes its progression suggests otherwise. As such, the show, up to this point, seems unsure about its own answer to Castiel’s question: “What would you rather have: peace or freedom?”